Yoshio Suzuki Interview

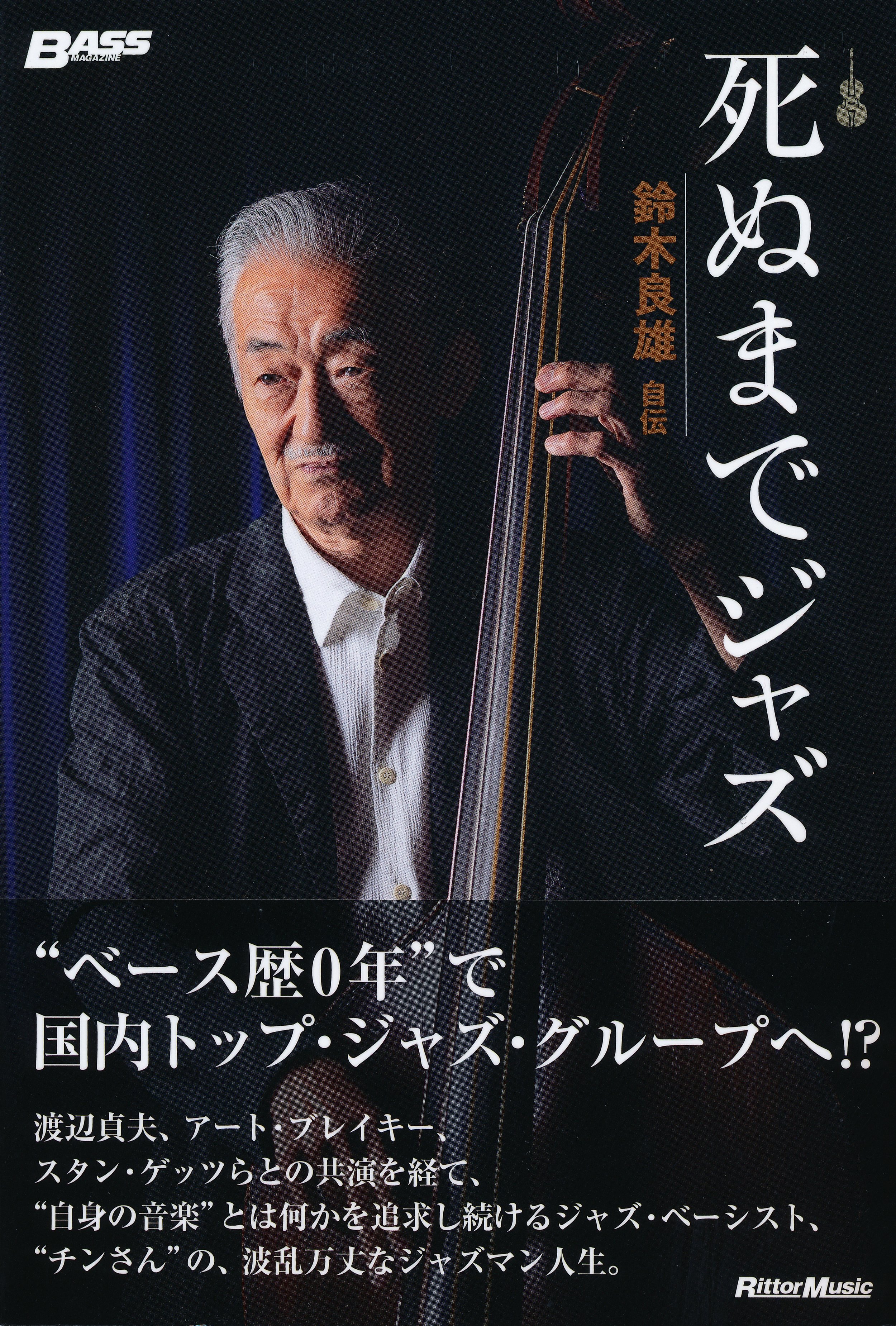

Yoshio Suzuki is one of the most established jazz musicians in Japan. He’s just released a book called 「死ぬまでジャズ」(roughly translated as Jazz Until Death) about his experiences learning music, switching to jazz, living and playing jazz in America, and working with musicians in Japan. He took time to talk about his life in jazz.

Pronko: Okay. So, tell me, how did you first hear jazz? You grew up in a musical family, so I picture you playing classical violin in a big room, and then suddenly you hear jazz. When was that?

Suzuki: That was when I was 17 years old. I was listening to classical. I love the romantics, Russian music like Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff. But when I heard Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five,” I said what kind of music is this? It's like seeing an abstract picture like Picasso or something. What kind of music is this? It's very interesting. At that time, I was playing guitar, like everybody does, and I was also singing with guitar, The Brothers Four. And we had a trio with another guy also on guitar. The other guy played maracas. And then after I heard “Take Five,” the maracas guy knew jazz a little bit. And I asked him, "You know, I heard the pattern last night. Do you know that?" "Oh, that's very famous," he told me. And I went to the shop and I got it. So that, that changed everything to carry that Dave Brubeck home.

Pronko: I’m sure it did.

Suzuki: But before that, my sister went to the classical conservatory. She was about five years older. She studied classical violin but sometimes, she'd have chansons and American movie music. Classical music is kind of a heavy background. I heard Bach, Mozart. Kind of heavy, right? Like, American music is so open, right? And my sister loved that kind of music. And then I went to Waseda University, and there was kind of a welcome concert for the new students. And there was something like a modern jazz group. I told them I was very interested in music, modern jazz music and the guy said, "Oh, yeah, come in next week." And that was like opening Pandora’s box. (Laughs).

Pronko: And then you were in the Waseda jazz circle? So that was like a big band or also small groups?

Suzuki: I joined a combo. And at that time, I got to play piano a little bit, and I was copying Brubeck, “Take Five,” and also you know Blue Rondo a la Turk” (singing).

Pronko: (singing)

Suzuki: I copied it out. And when I went to the practice room and people said, "I can't play this. I don't have the ability," I said, "I can't play any jazz, either." I was playing guitar, but I never could play jazz at all on guitar. And then I said at the last minute, I said, "Oh, I can play piano a little bit." And I played a little and they said, "You were great. You should play piano." And I said, "Okay."

Pronko: After you graduated from Waseda, you just played jazz or did you work?

Suzuki: Well, I never studied at university. I just went to the circle room everyday to play piano, have a jam session. In the nighttime, most days, we went to Shinjuku to a jazz coffee shop.

Pronko: To Dug?

Suzuki: Yes! Such good sound and with only one coffee, I stayed three hours. It was great. I studied every day.

Pronko: So, when did you switch to bass?

Suzuki: Actually, the bass is kind of a minor instrument in Japan, so people don't pick up the bass that much. I wanted to play trumpet. I wanted to play drums. “Anybody want to play bass?” It was not popular at all. “OK. I'll do it.” I could play bass because I played guitar. Same tuning, I thought, right? I had started violin when I was three years old.

Pronko: Violin and guitar are kind of like bass?

Suzuki: Not really, but you know, with blues, like “Autumn Leaves” or “Summertime” or something, I could do it just playing around.

Pronko: But there must be a moment where you must have started to love the bass. Or you still feel like bass is the last choice?

Suzuki: For me, it not a big thing to choose an instrument. Anyway, I love music, so always I play piano. But then there were no bass players, so I didn't care that it's an instrument that doesn't do much, because I never thought I was going to be a jazz musician.

Pronko: So for you, it's more like okay, I'm playing music. Or I'm in the music, so it doesn't matter.

Suzuki: It doesn't matter. As a musician, I never think about that. I'm like the water in the river. In the stream, it’s OK if you go here, okay if you go there. And at the last minute, go to the ocean.

Pronko: But later, you went to New York to hear jazz, right? So, when you went to New York, the reason was jazz?

With Sadao Watanabe at Newport Jazz 1970

Suzuki: Yeah, of course. When I almost graduated from university, I met Sadao Watanabe, the saxophone player. He had come back from America where he studied at Berklee School of Music, and learned the theory of jazz. Many huge Japanese musicians went there, Toshiko Akiyoshi and then Sadao Watanabe.

Pronko: So, you also did?

Suzuki: I joined the jazz classes and I learned a lot of the same theory. But mostly I studied myself by ear and from records. Nobody taught me the harmonization and information about melody, but the hardest thing is harmony. The jazz harmony is complicated. I always wondered, how do they get that kind of sound? So when I met Sadao, mostly I knew it already. And I just made sure oh, this, is this, right?

Pronko: I talked to Toshiko Akiyoshi once a long time ago, and she said the same thing. She would go to Chigusa in Yokohama and she would just ask him to play one part over and over.

Suzuki: You know, different people go to school and think that oh, this harmony's right [singing a melody]. But for us, just to catch up to the harmony is the hardest thing. So, I got a tape recorder.

Pronko: So you can rewind?

Suzuki: Yeah, but just only a second. Stop it. And then wait, that harmony is maybe different? And you find out, oh, this is it, you know? That kind of thing day by day, I studied.

Pronko: So, you did all of that before you went to New York?

Suzuki: Right.

Pronko: And then in New York, did you study more, or you were just playing?

Suzuki: Just playing. Just playing. I studied classical composition, because if you want to play jazz, you have to know the theory. But that's later.

Pronko: So New York was a great experience or coming back was a great experience? Or how did you feel at the time?

Suzuki: Yeah, well, that was important to me in my life. I was still just deciding the path of my life. But I was taught everything in New York in those twelve years. Everything, the culture and people, that way of thinking and playing music.

Pronko: And what made you come back, then? Just money, pressure, the craziness of New York?

Suzuki: I always say, I love New York, but I hate New York.

Pronko: Yeah, I know that feeling. It's crazy, right?

Suzuki: But I wanted to stay, very honestly, but there was a lot of racial discrimination, too. I felt it.

Pronko: Oh, definitely.

Suzuki: Not so much for the Japanese, and the white people at Berklee were so different, but still, this is very heaviest side of America. That's what I felt there. That's why that kind of jazz music came out. And at that time, I was single still, you know? So before I met my wife, it was so hard living alone in New York. I was talking to myself in the mirror. "How are you? Okay." That was crazy.

At Seventh Avenue South with Kazumi Watanabe guitar, Andy LaVerne piano, Chuck Loeb guitar

Pronko: New York is great, but it's also cold and—

Suzuki: Aggressive. In Japanese, we never show the aggressive part. It’s always, “Domo, sumimasen,” in Japan. But that's why I came to understand a lot of different parts of the humor and the people and the country. The way of thinking. I loved all that though. That city is special.

Pronko: So that was, like, in '70, '73?

Suzuki: '73 in the autumn.

Pronko: And then you came back to Japan when?

Suzuki: 1985.

Pronko: So, when you came back from New York, that's kind of the bubble years, right? Lots of jazz clubs and lots of places to play and things. Did you feel culture shock coming back? How did you feel when you got back to Tokyo?

With Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers at the Village Gate 1974

Suzuki: I came back here sometimes so there was no shock. I came back with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers. I was so lucky I got there in New York in 1973. Bob Cranshaw, who played with Sonny Rollins, couldn’t make the tour and asked me, "Do you want to go?" I said, "Yeah, sure." That was like a couple months after I went to New York City.

Pronko: That was easy.

Suzuki: That was lucky. At that time, we had some jam sessions with American musicians and a drummer got some gigs in Brooklyn. And she said, "Are you going to make it?" I said, "Yeah. I’ll show up." I went there, and the piano player Albert Dailey, a great piano player. So after we finished the gigs, he asked me, "I'm playing with Stan Getz now and he is looking for a bass player. You want to audition?" I said, "Yeah, why not?" And I went there and played a couple of things, and he said, “Yeah, let's do it.” And that's like a couple months after I get to New York. It was Stan Getz, you know?

Pronko: That's amazing.

Suzuki: I was playing with Sonny Rollins when the office guy called me, “Hey, Chin, we're going to California next week? You want to join?" I said, "Why not? Let's go." And I joined the Stan Getz group. I never can forget it.

Pronko: He's amazing.

Suzuki: The first gig was at Shelly's Manne-Hole in Los Angeles. And that's the first time I worked with Stan Getz. And I went to California and rich people would hire the whole band, for some big parties. And it got a bit rowdy.

Pronko: Like at a huge mansion?

Suzuki: Not a mansion. A castle. Like the people said, "Oh, this is the gate." That's the place, right? Then mountains, and ten minutes later, the castle. With a fountain.

Pronko: That's amazing. So that was a great experience.

Suzuki: I wanted to play more, and go to Europe, but I didn't have a permanent visa so I couldn't go out of the country. I already applied for it, so you have to wait and can’t go out. So, I said, "I can’t go to Europe."

Pronko: But then you played with Art Blakey.

Suzuki: That was a crazy time with Art. That was heaven and hell.

Pronko: So, was it crazy because of Art Blakey or the touring is crazy or both?

Suzuki: Ah, both, both. He never stopped playing. He always keeps playing. We went on the tour and after a couple months, he said, "I have not even got to New York.” So we just played New York—he never rested. He was just kind of a worker bee. Art taught me a lot, you know?

Pronko: But you learn by ear more, right?

Suzuki: I was with Art Blakey for two and a half years. A long time. At that time, his golden age was kind of finished when I joined his band. Because the front used to be Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Cedar Walton, great musicians.

Pronko: So is that because of drugs, travel, money…

Suzuki: I don't know. Just the times go on. He always educated the young musicians. Like he mentored everybody. He said, "Come on. Come on." And very great musicians were gone. They went off with Miles Davis. And that's why I felt like Art Blakey’s music was already old. But when I went to play with him the first time, I said, "Wow, this is a great sound. Great music. He can play." New drummers were coming in like Jack DeJohnette, but what I thought was old style was really just “Wow.” I never heard this kind of sound.

Pronko: So when you came back to Tokyo, then, how did you feel playing with the musicians? Were there people you could play with that you liked to play with?

Suzuki: Playing with Japanese musicians, of course we have a common sense, a common feeling, more easy. To play with black people and also white American musicians…it's different. The simple difference is American musicians, all musicians, have a good sound. They know how to play the instrument. And here, sometimes people play too much. But we have a common feeling, so I don't know which is better. The really big difference is time feeling. Time feeling is the most difficult part. Jazz and Japanese traditional music, has the same kind of groove. But the time is kind of the opposite style. Because when we feel that that two and four, the accent, we get tired. But one and three, I could do it all night. That's more from deep culture. The only difference with Japan is one note. Flat five. We don’t have that. That’s jazz.

Pronko: That has to be there, yeah.

Suzuki: Many, many differences, but many, many things in common. Why jazz music is so strong and so rich, is because European harmonies and African beat marry. In jazz, the music of white people and black people have married. All the music around the world has ‘melted’ together. All other ethnic groups felt the same thing, and now any kind of music can be jazz. I think this is the right way to proceed for mankind, for human beings. At last, race doesn’t matter, and I hope there will be no more wars. This is my ideal.

Pronko: Jazz lets everything in. Everything.

Suzuki: Right, anything is fine.

With Toshiko Akiyoshi

Pronko: Jazz I always feel is a kind of form like the novel or like film in which everything can go inside. It's a strong structure, right?

With Bill Hardman (trumpet), Junior Cook (sax), Mickey Tucker (piano)

Suzuki: That's a great way to think of music.

Pronko: So jazz musicians in Japan now, especially younger musicians, are really great. I mean, of course, your generation was great to break the ice and create this space. Do you feel a big change in the musicians?

Suzuki: Well, actually, when I listen to the young musicians and I'm playing with them, they're so great, but they don't let their personalities come out. Like notes and the sound, it's perfect. Time is perfect. But who are you? They don't have an individual sound, like Miles Davis. I hear him, and in one second, I will know, "Oh, it's Miles. Oh, this is Coltrane." I think that's very important that music has personality. In my generation, we were looking for who we were. We were looking for—

Pronko: Identity.

Suzuki: Yeah. I want to do something only I can do. Only me. Only I can do it. That's what I want to do. The young musicians studied well, and at many colleges and universities, they teach everything there is.

Pronko: Theory, playing, practice.

Suzuki: Study's like somebody's already done it, so that's education, right? But jazz music, its creation, like nobody did it before. We have to go there. That's the hardest part, to create new music. If they haven’t spent much time on creating something by themselves, they sometimes lack originality and sound the same.

Pronko: Some musicians who are also teachers say their students don’t go to museums or go see movies. They only experienced jazz, so they can’t convert their experiences into music. That’s what you mean?

Suzuki: Yes, yes. What is art? They are not really thinking about it. That’s why I don’t see many messages when I hear the music of young musicians. The surface is good, but the deeper message is not there.

Pronko: No, I feel that too, sometimes. If you don't connect, nothing else matters, right?

Suzuki: That's the most important thing, deep communication, the inside. And they are not trying to get what is art. I feel like the surface is perfect. But then I ask, "What is the message?" They all say, "Oh, I know this. I know this song.” But that's not the way. Creation, art, is very deep, very human. It’s a kind of beauty that includes philosophy, space, religion. Nobody knows what that is, you know?

Pronko: But music is one way to find some answers, right? Or maybe not to find the answer, but to keep looking for the answer, or try to feel the answer or think about it.

Suzuki: That's why have religion, music, art, everything that people are creating. That's why I feel creators use space and time and their own ability to find different music, or different painting or new art. There is no limit. But if you just repeat, then some new thing is never created. So you have to find something new. That's not easy, though.

Pronko: No, but that's very important.

Suzuki: Because I'm writing a tune that's not easy to learn. It's always like searching, being able to play piano for thirty minutes, and in that thirty minutes, you just find one note. You find that, and think, oh, what is this? Oh, this is something. That something is a tiny little piece of something more, and then we can—well, it’s slow going. It's not easy.

Photos courtesy of Yoshio Suzuki

“Shinu Made Jazz” released 2024

Yoshio Suzuki’s website: https://chin-suzuki.com/

(Spring 2023)